Study hard, and you'll get into the college of your dreams.

It's debatable whether that advice -- given to generations of American children -- was ever really true. But the first

Inside Higher Ed

poll of parents of pre-college students suggests that the truer

statement today might be "study hard and you can get into the college we

can afford," or perhaps "study hard, and we'll help you get into a

college that can find you a job."

Only about 16 percent of parents are sure they won't restrict

colleges to which their children will apply because of concerns about

costs (although another 14 percent said that it was "not very likely"

that they would do so), the results show. Parents are also likelier to

see vocational certificates than liberal arts degrees as leading to good

jobs for their children -- and they view job preparation as the top

role for higher education.

And at a time that a case before the Supreme Court could limit the

way colleges use affirmative action, the poll found that most parents

(including most white parents) do not believe that affirmative action is

costing their children spots in college.

Parental concerns about paying for college and the importance of

college programs that prepare students for jobs appear to grow as

children get closer to college age, the poll found.

The poll was conducted for

Inside Higher Ed by Gallup as

part of the polling organization's nightly poll of Americans on a range

of subjects. These results are based on responses from 3,269 adults with

children in the 5th through 12th grades. According to Gallup, the

sample size yields a 95 percent confidence that the results are accurate

within two percentage points. Margin of error may be larger for

subgroups of the total.

A booklet with all of the survey data, plus related articles from

Inside Higher Ed, may be

downloaded here.

Sticker Price Still Matters

For decades now, a consistent message from college and university

leaders has been that potential students should not be scared off by

sticker price, and should be open to applying to even the most expensive

of colleges (judged by the rates for tuition and other expenses),

knowing that so many colleges offer generous financial aid. To judge

from the survey results, this message is not getting through in a

consistent way to parents.

Two-thirds of parents say they are very likely or somewhat likely to

restrict the colleges to which their children apply -- meaning that

these future students may never know of the potential of financial aid

to reduce the payments expected of them and of their families. And the

likelihood of parents restricting colleges to which their children can

apply goes up as the students get closer to college age.

Will Parents Restrict Colleges to Which Children Can Apply, Based on Tuition?

|

Response |

Child in 5th-8th Grade |

Child in 9th-12th Grade |

All |

|

Not at all likely |

17% |

16% |

16% |

|

Not very likely |

17% |

13% |

14% |

|

Somewhat likely |

31% |

36% |

34% |

|

Very likely |

33% |

34% |

34% |

Richard Ekman, president of the Council of Independent Colleges, said

that the results should be "a wake-up call" to college leaders. Despite

all the talk about the variety of ways that exist to pay for college,

most parents remain unaware that tuition sticker price is not the only

important number.

"We have to get people past this affordability mental block," he

said. He said that there is a "tremendous amount of aid" being offered

by colleges where the sticker price has very little relationship to what

most students pay. Somehow colleges have failed to make people

understand this, and parents are a crucial audience to reach, he said.

"I think that too many of us in higher education may assume that certain things are understood," he said. "They aren't."

Ekman said cost concerns relate to several economic issues. "Emphasis

on jobs and on affordability has been building for a very long time,"

he said. "What's new is the tremendous acceleration of the emphasis of

jobs at the same time there is a tremendous emphasis on affordability.

And this is a direct consequence of the economic meltdown."

While this survey is new, and doesn't have past years for comparison

purposes, it is clear that jobs are very much on the minds of parents.

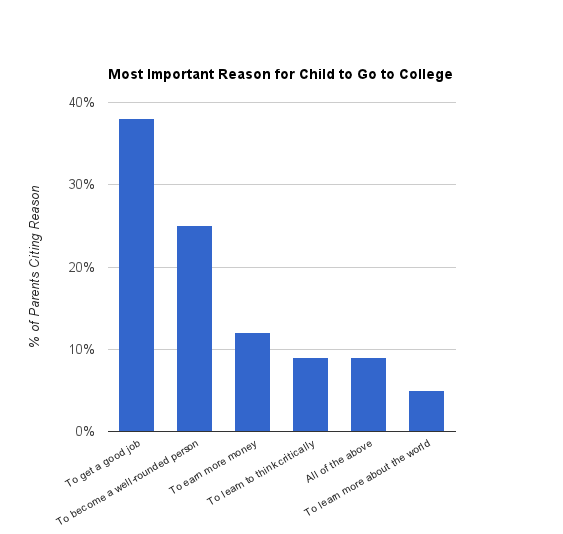

Parents were asked to identify the most important reason for their

child to go to college and the top answer by far (at 38 percent) was "to

get a good job." The third most common answer (at 12 percent) was "to

make money," while answers associated with more educational reasons

lagged. Parents were given an option of "all of the above," but

relatively few took that option.

Breaking apart the data into those whose children are closest to

going to college suggests that parental anxiety over jobs grows during

those years. Consider the shifts in the top two answers. Of parents of

children in 5th-8th grade, 35 percent said "to get a good job" was the

top reason to go to college. But the figure rose to 41 percent for

parents of 9th-12th graders. And the percentage saying that "to become a

well-rounded person" as the top reason fell from 27 percent to 24

percent.

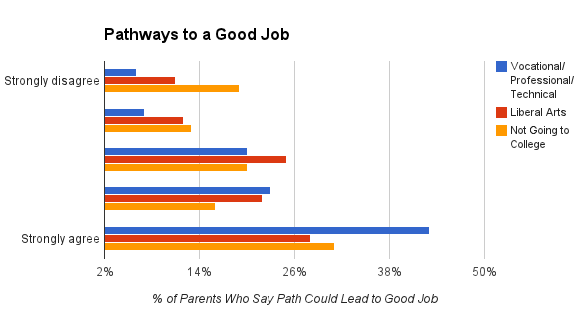

Potentially alarming to colleges is that many parents do not believe

that going to college is a necessary step to getting a good job --

notwithstanding what President Obama and many educators would say,

citing

plenty of data to back up their points. In recent years a growing number of pundits and politicians have

questioned the idea that everyone benefits from college -- and the

Inside Higher Ed poll results suggest that some parents (a significant minority) agree with this critique.

Parents were asked to respond to the statement: "I am confident that

there are ways other than going to college that could lead my child to a

good job." On a five-point scale, where 5 was "strongly agree," 31

percent answered 5, and another 16 percent answered 4. Only 19 percent

strongly disagreed.

Parents were also asked whether they believed a liberal arts

education or a vocational/technical/professional program would lead to a

good job. The results show that parents are more likely to strongly

believe that no college at all can lead to a good job than to believe

that a liberal arts education can lead to a good job.

For many education leaders who promote the idea of liberal education

(and who don't see that as inconsistent with preparing for careers),

some of the responses are frustrating.

Carol Geary Schneider, president of the Association of American

Colleges and Universities, said that she viewed "all of the above" as

the "correct answer" on the purpose of college. But she said that the

results reflected the reality that many people believe in a dichotomy

between education that prepares one for a job and education that

encourages critical thinking and other valuable qualities.

In particular, she said that there is a problem for liberal arts

colleges and disciplines in that there is a "very confused and

ill-informed understanding of what one means by the liberal arts" in the

public at large. The AAC&U has conducted a series of surveys of

employers on what they look for in college graduates, and has a new

survey coming out next month.

Those results, she said, will mirror past surveys in showing that

employers are very concerned about whether new hires are critical

thinkers, understand the world, know how to solve problems and work with

others, and so forth.

A majority of employers surveyed think that these qualities are "more

important" than the major, she said. But much of the current discussion

about careers suggests that all that matters is picking a job-specific

field of study. "Too many people think that the major is all that

matters, and everything else is irrelevant.... What employers are really

looking for is that they want to know that students can apply their

learning to new settings and to complex problems," and that can be true

of any number of majors.

Ekman of the Council of Independent Colleges agree that part of the

problem is that the public doesn't really know what a liberal arts

college is any more -- and that liberal arts colleges describe

themselves in different ways. "There are very few so-called pure liberal

arts colleges," he said. "Almost every college that calls itself a

liberal arts college offers a few professional programs, and general

education, and that's a very good model."

Schneider, however, also faulted politicians, the news media, and

academic leaders for seeming to accept the idea that narrow education

with a job focus is the best kind. "I think policy leaders and public

officials who should know better are contributing to the public

perception," she said. "The ill-advised rush from the Obama

administration and state capitals to track the return on investment of a

particular major is simply reinforcing outdated thinking."

Not only will people be better off over their lifetimes with a

broader education, but so will the country, she said. "The academy needs

to be more courageous that there is a fundamental connection between

liberal education and future of democracy," she said.

Others, however, say that colleges can do much more to help students prepare for jobs.

Wake Forest University has

greatly

expanded career counseling offered to all students, with formal

courses, more advisers, and a constant flow of information on career

paths. Parents have started to donate money for career services, and other colleges send teams to study the Wake model.

Andy Chan, vice president for personal and career development at Wake

Forest, said that the emphasis parents are placing on jobs shouldn't

surprise or necessarily alarm anyone. "I think it's indicative of what's

happening in the general market place and the anxiety families feel,"

he said. "When I think about it, if colleges really invest in personal

and career development, and show the connection and the actual outcomes

of what getting a liberal arts education can result in, and show that

there's a lot of support, then parents will feel better about investing

in a liberal arts education."

Chan said, however, that too many colleges and too many programs

don't provide the services or the information that will reassure

parents. Wake recently started publishing person-by-person job titles

for academic majors. The names are not given, but the year of graduation

is, along with the city. For art history, for example, one would find

that recent graduates are employed as a "tasting room associate" in a

winery in Napa; an English teacher; a curatorial assistant; and so

forth. Many are in graduate school (with institutions named); one is an

au pair. "When you gather the information, there is a lot of good news,

but most places aren't telling the story," he said.

Loans? Don't Be Sure You Can Count on Mom and Dad

While parents are very worried about their children getting good

jobs, only some are willing to borrow money themselves to pay for their

children's higher education.

Inside Higher Ed asked the parents

how much debt they would be willing to accumulate for a four-year

degree for a child. Some are willing to take on quite a lot of debt --

with 21 percent saying that they would consider borrowing $50,000 or

more. But nearly as many (20 percent) said that they were unwilling to

take on any debt, and another 7 percent would not consider debt greater

than $10,000.

For this question, there appears to be a relationship between parent

reactions and parent income. Of those who earn at least $7,500 a month

($90,000 a year), 31 percent would be willing to borrow $50,000 or more.

Of those with family income up to $3,000 a month, only 11 percent would

be willing to take on that level of debt.

But those earning $7,500 a month or more were also more likely than

those earning up to $3,000 to say that they would take on no debt for

their child's education (21 percent to 19 percent).

Affirmative Action: Who Loses?

Inside Higher Ed surveyed parents at a time of growing public debate over affirmative action in higher education. The Supreme Court has

heard arguments

but has yet to issue a ruling in challenge to the consideration of race

in admissions by the University of Texas at Austin. While the case

could be decided narrowly about the policies at Texas, it also could (if

those suing have their way) lead to limits or a ban on consideration of

race in higher education admissions. The case was filed in the name of

Abigail Fisher, a white woman whose lawyers say that she would have been

admitted to UT-Austin but for its consideration of race. Critics of

affirmative action talk regularly about Fisher and people like her,

suggesting that individuals are being excluded from elite colleges for

not being a member of a minority group. (Of course, the evidence of the

impact of affirmative action on any one individual isn't easy to

determine and

many argue that Fisher wouldn't have gotten into Texas even without programs that consider race.)

Given the political significance of the debate,

Inside Higher Ed

asked parents whether they believed that affirmative action hurt their

children's chances of admission to college. Only a minority of American

parents (and only a minority of white parents) believe that this is the

case. (A key caveat: Gallup officials did not consider that their

sampling of Asian-American parents was large enough to draw conclusions

about their views, and

Asian-American groups have been split on affirmative action.)

The results below show that there are minorities of black and Latino

parents who believe that their children's chances of admission are hurt

by affirmative action. But black parents were far more likely than other

parents to strongly disagree with the statement that their children's

chances of admission were hurt. The results suggest parents may be aware

of one of the points made by defenders of affirmative action: that most

students get into the colleges they apply to, and that there are only a

small proportion of colleges with highly competitive admissions for

anyone.

Parents on Whether Affirmative Action Hurts Their Children's Chances of Admission

|

View |

All |

White |

Black |

Hispanic |

|

1 (strongly disagree) |

27% |

23% |

53% |

26% |

|

2 |

15% |

17% |

9% |

15% |

|

3 |

23% |

24% |

15% |

25% |

|

4 |

13% |

13% |

7% |

16% |

|

5 (strongly agree) |

20% |

23% |

16% |

18% |

Doug Lederman contributed to this article.

No comments:

Post a Comment